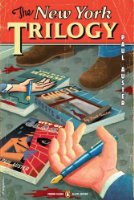

Title: Ghosts (Book Two of the New York Trilogy)

Title: Ghosts (Book Two of the New York Trilogy)

Author: Paul Auster

Year of Publication: 1982

LC Call Number: PS 3551 .U77 N49

Ghosts is the second book of the New York Trilogy, and at around seventy pages, it’s the shortest of the three. In many ways, it resembles City of Glass. Each book has as its protagonist a detective/writer who is assigned to follow another man, whom he does not understand. In each case, those who assign the case are shadowy and impossible to contact, and in each case, this task of watching someone else ends up being the protagonist’s undoing.

Ghosts has a somewhat different denouement, but the most obvious difference between the two works is really stylistic. City of Glass featured a set of characters whose names change hands over the course of the novel and don’t clearly belong to anyone. The characters in Ghosts get to keep their names (with a few exceptions), but the names they are given are somewhat interchangeable. The detective protagonist, Blue, is observing a man named Black on the orders of the mysterious White. Blue was trained by Brown, who is now retired, and has come to this point in his career after capturing the embezzler Redman, and solving a case involving the amnesiac Gray, who after losing his memory took on the name of Green and remarried his original wife, who also changed her name from Mrs. Gray to Mrs. Green. Blue would like to be more like Gold, who has pursued the case of a mysterious dead child for years, even after his own retirement, but is instead stuck tailing Black on this meaningless mission he has been given.

What is this, I said to myself, a game of Clue?

Well… not exactly, because after all a game has an unambiguous ending with clear winners and losers, and yet it does almost feel like a game. Auster does make more of colors than simply using them in the names, pointing them out at odd moments that made me wonder whether it was specific to this work or whether colors are always mentioned in this way but I am simply more sensitive to them because the naming scheme is so odd. But, maybe because I spend, ahem, a non-trivial amount of time playing and thinking about board games, it was difficult for me to stop thinking of it in this way once I had begun. It’s fairly common when discussing sessions of games to refer to players by their player color, especially when one does not know them well or is not interested in them as people so much as a series of moves on a board. As far as this goes, it is a somewhat reasonable way of considering the relationship between the reader and the characters in this book. Of course, if you think about it carefully, all fictional characters consist of a series of actions performed in a space with clear boundaries, but the naming conventions of Ghosts underlines this reality. We have insight into only one position, Blue’s; that is the one which we are, figuratively, “playing.” We get to know Blue fairly well, because we live in his head, but our main concern for him isn’t exactly his fragile psyche so much as what he should do next. All around him are characters who take certain actions which he needs to predict so that he can react properly, but he’s rather bad at that. To be fair, of course, some of them behave in ways that are also surprising to the reader. There are no clear victory conditions that we can understand, so of course their actions remain obscure to us. What is clear, however, is that Blue does not win.

Of course, there are some limitations to this reading. The characters are not competing for the same goals but all seem to have distinct victory conditions. Some are allotted more moves than others, and some seem already to have left the game. Blue appeals to Brown for assistance, but is refused because Brown will no longer participate. Gold has decided on his own that he only cares for this one case. And by the end of the game, we learn that there is collusion between two of the players, or rather, that one player is controlling two “pieces.”

Still, if that doesn’t quite work, it does point out the reader’s distance from the story. City of Glass gave us a protagonist whose psychology we could consider, even if we didn’t fully understand it. It felt like something that, strange as it was, was happening to people in the world. Ghosts takes almost the same story, with some trivial differences (Blue is a detective turned writer rather than a writer turned detective, the ending is different and more detective-y, etc.), but removes some of the plot complexity, turns the characters into ciphers, and generally flattens it out into an example of the genre. Meanwhile, the story adds things like Blue’s reflection on the meanings of colors. So, although the earlier story was already fairly unsettling, this one makes it even more so by stepping back. The relationship to other texts is still there, but now it’s all about Walden. Blue’s character arc is at least partially about learning to read Thoreau. I haven’t read Walden, so it’s difficult for me to comment on the work it’s doing in this text, but… certainly it can be said to simplify?

In any case, there’s a refusal to get under the surface of the characters. As Blue doggedly tries to plumb the depths of Black’s character, he spends most of his time watching Black reading, and reflects that this is essentially the same as doing nothing, until eventually he begins reading himself. In a way, watching someone read is the ultimate experience of alterity; the person that you are observing is having an experience of which you absolutely can know nothing. Strangely, and much like Quinn in City of Glass, Blue is for some reason unable to simply give up and go home. There is no obvious reason he should stay; he’s getting paid, but he could just as easily get paid for doing the type of work he prefers. There’s no coercion, either. Instead, he stays at his post, long after he’s realized that he is the victim here. He comes to identify with Black, because he is trying so hard to get inside his mind, by doing the same reading and by watching him, and finally, by breaking in and reading the notebook in which Black has been writing with a red pen (there must always be a red notebook of one type or another). In the end, all he really learns is that Black and White are the same. He’ll never understand either one of them, and his only recourse is to violence. Even reading the notebook doesn’t help—he recognizes that he already knows what it contains.

At the end, the story dissolves, and the narrator simply shrugs: “I like to think of Blue booking passage on some ship and sailing to China. Let it be China, then, and we’ll leave it at that.”

To like or dislike such a book really seems beside the point; the most I can really say about it is that it adds something to the possible readings of City of Glass. How separate are the three books of this trilogy?

That is a really interesting look at that story. Love the idea that they are pawns, of sorts, but in a game that has varying goals or “wins” for each player. Very cool. Don’t doubt my hatred for this book, but you win for making me think about it differently. 🙂

Thanks 😀